In our last episode, we talked about the Parker Solar Probe. As always, we like to talk about the person who inspired the mission. What makes this amazing and different is that Eugene Parker was there to watch the launch of the mission that shares his name. Why is he so influential on solar astronomy?

Show Notes

- Eugene Parker’s early career

- Eugene Parker’s contributions to the field of heliophysics

- The Parker Solar Probe

- Eugene Parker’s later life

Transcript

Human transcription provided by GMR Transcription

Fraser Cain:

Join Patreon for an ad-free experience at patreon.com/astronomycast. Astronomy Cast, episode 728, “Eugene Parker.” Welcome to Astronomy Cast, our weekly facts-based journey through the cosmos where we help you understand, not only what we know, but how we know what we know. I’m Fraser Cain. I’m the publisher of Universe Today. With me, as always, is Dr. Pamela Gay, a senior scientist for the Planetary Science Institute and the Director of CosmoQuest. Hey, Pamela. How are you doing?

Dr. Pamela Gay:

I – I am doing well. I am super excited. On October 4th, I’m giving a talk at the St. Louis Science Center. And it’s during one of their themed events, and the theme for the night is Barbie and STEM careers. So, I – I’m going to – they – they encourage cosplay. So, I have a pink suit and a pink dress. And – and I’m, uh, going to have – my first slide says, “My job is space.” Um, and I’m gonna talk about all the women throughout history who, uh, have basically done groundbreaking work while being citizen scientists. Um, yeah. So, I’m super excited about that.

Fraser Cain:

That sounds great. Um, so, I am also excited. I – I haven’t mentioned this to you, Pamela, yet, but, um, I’m gonna be taking a trip after we record next week. So, I’ll be here next week but then I’ll be gone. I’m going to, uh, Europe for –

Dr. Pamela Gay:

Oh.

Fraser Cain:

– eleven days with my kid.

Dr. Pamela Gay:

Okay.

Fraser Cain:

So, the other kid. And so, I took my first kid to Japan, and now I’m taking my second kid to Iceland and Amsterdam. And so, we are gonna be in Iceland for three nights and then we’re gonna be in Amsterdam for the rest of the time. Early October –

Dr. Pamela Gay:

Does that mean we need to record two episodes next week?

Fraser Cain:

Maybe. But, you know, – or maybe I can record them while I’m afar. Maybe. We’ll figure that out. Um, but – and the goal is to see the auroras, to – to be able to be in Iceland and actually watch as we increase toward solar maximum. So, I’m pretty stoked and, uh, I’m looking forward to going back to Europe.

Dr. Pamela Gay:

Amsterdam is one of my favorite cities. If I was –

Fraser Cain:

It’s such a great city.

Dr. Pamela Gay:

– offered a job in the Netherlands I’d move in a heartbeat.

Fraser Cain:

Yeah. So, last week we talked about the Parker Solar Probe, and as always, we like to talk about the person who inspired the mission. What makes this amazing and different is that Eugene Parker was there to watch the launch of the mission that shares his name. Why was he so influential on solar astronomy? So, this is – you were quite excited about this –

Dr. Pamela Gay:

Yeah.

Fraser Cain:

– when we were talking about the Parker Solar Probe and you were like – and you often would say, “And by the way, he’s still alive. Isn’t it so adorable to watch him there at the launch site watching his spacecraft take off.” So – so – and he is passed away now but – but normally –

Dr. Pamela Gay:

He was alive for the launch.

Fraser Cain:

– normally, the people who the spacecraft are named after have been – have passed away for a long time. And in some cases, hundreds of years, thousands of years, in some cases. And yet, he was there for the launch. So, who was Eugene Parker?

Dr. Pamela Gay:

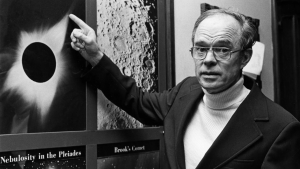

He was a physicist who, uh, – so, I’m pleased to say, we have the same alma mater. We both went to the physics department at Michigan State University. He just did it half a century before I did. Um, he was a physicist, and his work ended up opening up the field of heliophysics. It didn’t exist before him. He – he finished his undergraduate degree 21, 22. I couldn’t tell what date he graduated. Um, he then went to, uh, Cal Tech to do his PhD, which he did in three years, which blew my mind. He was then an instructor at the University of Utah for a few years before going to the Enrico Fermi Center at the University of Chicago, where he did the rest of his career.

And as a baby professor, he postulated that the sun could have a magnetic field that triggered a solar wind. And when he submitted the paper for this, the referees, one of them literally said that he needed to go to the library and read more because the paper was ludicrous. Um, the paper was soundly rejected by both referees, but the editor of the journal was Chandrasekhar, who was also at the University of Chicago, knew Eugene Parker, and he reviewed the math. He replicated the math. He could find nothing wrong with the math. So, he published the paper anyways. And – and so, that was 1957, and I have to look at my notes to get all the dates right. So, the paper was published in 1957. This was before we really had a lot of space probes.

And in 1962, Mariner 2 on its way to Venus measured the solar wind and all the people who were still making fun of Eugene Parker for his ludicrous idea, um, had to agree that he was right. And since then, the particular research paper that he published, the one that was soundly rejected with scathing criticism, has over 4,000 citations.

Fraser Cain:

Wow.

Dr. Pamela Gay:

It’s just amazing work.

Fraser Cain:

So, wait. Did he postulate the existence of the solar wind based on the magnetic field of the sun? Like, he guessed the sun would have a magnetic field and therefore to be producing a solar wind? Or was he –

Dr. Pamela Gay:

Exactly.

Fraser Cain:

He wasn’t just suggesting that the source of the solar wind was the magnetic field?

Dr. Pamela Gay:

No. We didn’t know there was a solar wind at all.

Fraser Cain:

Wow.

Dr. Pamela Gay:

There – the solar wind was not to blame for aurora yet. I now want to go back and find out what they thought caused aurora up until this point because I have no idea.

Fraser Cain:

Yep. Yeah, yeah.

Dr. Pamela Gay:

Um, but, yeah. He completely postulated the – the – like, he’s also responsible for like the solar dynamo idea for magnetism and galaxies. And we can go into detail on all of this stuff. But in the 1950s, we didn’t know there was a solar wind. He looked at the math. He looked at the magnetic field of the sun. And he’s like, “Gotta be a solar wind.”

Fraser Cain:

Right.

Dr. Pamela Gay:

And he did all the math –

Fraser Cain:

Wow.

Dr. Pamela Gay:

– to prove it from first principles. It was amazing.

Fraser Cain:

Right, yeah. And when Chandrasekhar looks through your math and gives it the green light, that’s – I mean, he – he’s the guy who figured out the Chandrasekhar limit. I mean there’s – there was a documentary about him.

Dr. Pamela Gay:

So, Chandrasekhar – and go back and listen to the episode we did on him. Um, he was also soundly knocked for some of his principles until they were proven. So, he understood that sometimes you have to wait for someone to die before your theories get accepted.

Fraser Cain:

Yep.

Dr. Pamela Gay:

And he – Parker was so lucky to have Chandrasekhar in his corner.

Fraser Cain:

Yeah. That’s – that’s incredible. Um, so, like what else? I mean, so he – he made this groundbreaking sort of prediction –

Dr. Pamela Gay:

Yeah.

Fraser Cain:

– which – which are like the best. I mean –

Dr. Pamela Gay:

Yeah.

Fraser Cain:

– when someone predicts a thing in the universe and then someone takes a telescope or a mission or whatever and goes and finds that thing, those are the – some of the most impactful sort of advances in the science that have – that are ever made. You think about Einstein’s relativity. You think about, uh, various theories about black holes and so on. When someone makes that kind of a prediction and then the technology comes along to actually demonstrate that it’s true, it really stands the test of time. So – so, what else then, you know? How did he top that? What did he – what did he then go on to do?

Dr. Pamela Gay:

[Laughs] So, every biography I’ve found of him described him using either the word visionary or a, uh, synonym for visionary. And he went on to also postulate what is now called the Paker spiral, which he was a magnetic physicist. He wasn’t – the field of solar science, the field of heliophysics, didn’t exist and his work spanned multiple areas. He was a magnetic fields physicist. So, in looking at the sun’s magnetic field, which he continued to do, he realized that the rotation of the sun would cause drag on the magnetic field. And this had – there was drag between the two of them is a better way to put it. And – and this would have two impacts.

So, one thing he predicted was what’s called the Parker spiral. So, between 10 and 20 AU out from the sun, the magnetic field begins to twist. And so, if you look at the large scale structure of our sun’s magnetic field, it actually has a spiral structure to it. It’s an Archimedes spiral.

Fraser Cain:

Hmm.

Dr. Pamela Gay:

It’s that classic shape that appears in everything from snail shells to grand designed spirals. Well, it’s also in the – the magnetic field of the sun. And on the other side of that, he realized that one of the things that is probably leading to the differential rotation of the sun where we see the equator and the northern and southern latitudes rotating at different rates was probably the magnetic field having an effect on the surface as well. So, he was able to figure out these two different major components of what the magnetic field is affecting in our solar system, both on the solar system scale and on the solar scale. And that was amazing.

Fraser Cain:

Right. And he – I mean, he wasn’t just content to work on just the sun. He took this idea of interactions between magnetic fields and plasma to many different scales.

Dr. Pamela Gay:

Yeah. He was the person who figured out that there should be magnetic instabilities in galaxies. So, when you look at a galaxy, you – you can get up and down motions in things and they also have a magnetic field due to the spinning of the material around the black hole and the core that is parallel to the disk. And because of the orientation in the magnetic field, when you get material that is coupled to the magnetic field, when you have charged materials in the disk that is moving up or down, you will get an amplification of that movement due to the interaction with the magnetic field.

So, when we see these warps in disks, to explain that we have to look, not just at the gravitational interaction of something perturbing the disk, but also the magnetic fields’ effect on perturbing material in the disks.

Fraser Cain:

And – and this idea of – of – or this technique for measuring the magnetic fields around some kind of an object, this is all really brand new. Um, –

Dr. Pamela Gay:

Yeah.

Fraser Cain:

– where you can essentially measure the polarity of the photons, the radio photons, that are coming from some object. And there’s this – this incredible work Say Done by Meerkat. I know that’s one of your favorites.

Dr. Pamela Gay:

Yeah.

Fraser Cain:

Where they’re able to scan chunks of the sky, measure the polarity of the radiation, of the radio waves, that are coming from this area. And that is because the photons have been turned into – into various directions and, you know, causing this polarity that’s visible. And you can then map out the large – Alma does this a lot as well. You can map out the large-scale structure of the magnetic field lines around what you’re looking at. And – and this whole field of predicting these magnetic fields that – that you – the way they sculpt and create galactic wide versions of the solar wind all trace back to Parker’s work in doing the math and making these predictions.

It’s absolutely incredible. I mean, you know? It’s like if they come up with a spacecraft that’s also going to search for, you know, examine the large-scale galactic winds coming off the Milky Way, they’ll also have to call it the, you know, the Parker Galactic Probe or something.

Dr. Pamela Gay:

Yeah, it’s – he was a theorist who took the ideas behind magnetic field theory and applied it anywhere there could be charged material. And the sun was something he kept returning to over and over again. The – the corona heating problem, um, was one of the things that I – I think he played with the most, uh, later in his career in 1987 in looking at the coronal heating problem. This is what we talked about in the last episode where – where the outer most, most diffuse part of the sun is like millions of degrees. Very confusing. Um, and – and he was the one who postulated that nanoflares, small breaks in magnetic field lines that are carrying hot plasma, could release sufficient energy to heat the – the corona.

And – and these are things that the Parker Solar Probe was designed to go look for. And – and all these ideas, he was always out there saying, “Hey, I’m a theorist. This is what the math says. Observers, go prove me wrong.” And that is a terrifying place to be.

Fraser Cain:

Right.

Dr. Pamela Gay:

And when he was asked to provide advice to young scientists after having this entire career of over and over again predicting things and sometimes being mocked, his advice was, and I’m gonna read the quote, um, “If you do something new and innovative, expect trouble. But think critically about it because if you’re wrong, you want to be the first one to know that.” And this was advice he have in 2018 to early career researchers.

Fraser Cain:

Oh, that’s fantastic.

Dr. Pamela Gay:

I just love that idea.

Fraser Cain:

Yeah, yeah. You – if you’re wrong, you want to be the first to know you’re wrong. Yeah, that’s so good. Um, you know, I mean that idea, the nanoflares that you mentioned, right, like, he back in the ‘80s –

Dr. Pamela Gay:

Mm-hmm.

Fraser Cain:

– did the math. Predicted that there should be these miniature flares on the surface of the sun, scaled down versions of the big bright flares that – that we see every now and then. These are happening all the time and that they were responsible for the coronal heating. And then you get the detection and measurement of these nanoflares by both Parker Solar Probe and the solar orbiter exactly as Parker had predicted. We just didn’t have the technology –

Dr. Pamela Gay:

Yeah.

Fraser Cain:

– to – to sense them beforehand. And so, I think, you know, that prediction of his that was – I’m just doing some math here. Like, whatever, 40 years old, plus, was finally confirmed by the spacecraft that bears his name. Once again, he was right.

Dr. Pamela Gay:

Did – did you watch the Parker Solar Probe launch on NASA TV?

Fraser Cain:

Yeah.

Dr. Pamela Gay:

Were you scared for him?

Fraser Cain:

I mean, he was 90 –

Dr. Pamela Gay:

Ninety-two.

Fraser Cain:

Ninety-two when it launched. Yeah, yeah. Surrounded by boisterous engineers and people clapping and, yeah, he looked pretty frail already at the time. But he was there –

Dr. Pamela Gay:

He – he was there.

Fraser Cain:

– to watch it launch.

Dr. Pamela Gay:

And what I was scared for was – so – so, once upon a time, they waited until missions were launched to rename them. So, like, uh, the Ferme x-ray satellite was Glassed up until like four days after launch when it became Ferme. Um, and – and so, we saw that over and over and over again. And then they started naming missions before they launched because that gave you more of an emotional connection and made it harder for Congress to murder them.

Fraser Cain:

The spacecraft, not the people.

Dr. Pamela Gay:

Right, right. The spacecraft. So, this was particularly important for the Nancy Grace Roman telescope. Um, but we never, except for the Parker Solar Probe, have named something after someone living. And – and as I’ve talked about in the past, I – I had a mission I needed for my dissertation blow up right after launch.

Fraser Cain:

Yes.

Dr. Pamela Gay:

And so, that haunts me. And so, like, I’m watching the NASA stream and the whole time I’m like, “Oh, god. It’s gonna blow up. It’s gonna break his heart. He’s gonna have a heart attack.” Like, this was the worst case thing –

Fraser Cain:

Yeah.

Dr. Pamela Gay:

– that was going on in the back of my brain. Everything was fine. Nicole Fox, who is head of Helio at the time, was with him the entire time. Um, and in fact, after his retirement and after the spacecraft’s launch, she continued to send him data from the Parker Solar Probe for him to review.

Fraser Cain:

Oh, wow.

Dr. Pamela Gay:

This is a man who retired but just kept doing research.

Fraser Cain:

Yeah. And we see that a lot. I mean, it’s just there’s so many scientists –

Dr. Pamela Gay: [inaudible – crosstalk]

Fraser Cain:

Yeah, exactly. The scientists, they – they – they don’t retire. They die. They just keep working. Um, so, – I mean, we – we saw the launch of the Parker Solar Probe and he was still alive –

Dr. Pamela Gay:

Yeah.

Fraser Cain:

– but, uh, – and they – they had named it in 2017 after him. But then he did pass away in 2022.

Dr. Pamela Gay:

Yeah. He was age 94. Um, he was survived by his wife of 67 years.

Fraser Cain:

Wow, relationship goals.

Dr. Pamela Gay:

Yeah, yeah.

Fraser Cain:

Yeah.

Dr. Pamela Gay:

He had both a son and a daughter. And – and his son had some of the best stories. So, apparently, like, the kids growing up knew their dad was a scientist but didn’t really know what he did. They had no idea that he was famous at all. And apparently, he was someone that worked really hard to have a work-life balance and would tell his kids that anyone who’s working over 40 hours is missing out on life. This was someone who was very much your Great Lakes Midwesterner. He loved to camp. He – he loved to go hiking. And his hobby was woodworking. His son Eric said in an interview that pretty much all the furniture in the house was made by his dad.

Fraser Cain:

Wow.

Dr. Pamela Gay:

He was that kind of a woodworker. And he also liked to carve figures of famous people. And I tried but I couldn’t find any photos of these. And I – I really – I really wish I could because just the idea of this person, who as a scientist I hold in such esteem, imagining him sitting on his front patio. Like, who was he carving figures of that he considered to be famous?

Fraser Cain:

Yeah.

Dr. Pamela Gay:

That’s what I wanna know, um, and no one said anything bad about him that I could find. He – he was the kind of person that was described as – as humble, which makes sense with his kids having no idea what he did. He was someone who was described as willing to do and publish research that – that people didn’t believe initially. He took those risks. And so, he was constantly back and forth throughout his career of, “Oh, he’s such a visionary” and “Oh, that idea is kinda (insert negative phrase”. That’s such a hard place to be. And to remain humble while living in that kind of a dichotomy. Just – those – those are scientist personality goals. Um, yeah.

Fraser Cain:

Yeah. I mean, I had heard him described as somebody who – who was very creative, out of the box –

Dr. Pamela Gay:

Yeah.

Fraser Cain:

– thought of, you know, – understood the implications and the consequences of – of various observations to sort of figure out what happened next but then was very careful and, um, diligent in –

Dr. Pamela Gay:

Yeah.

Fraser Cain:

– in how he explored the mathematics for what that would imply and was willing to throw out – as you say, as soon as you figure out you’re wrong, get rid of it. But – and then when you balance that with that – that perspective on work-life balance on – on shunning workaholism, and instead, build a career where you’re still thinking about – as you said, you know, even when he was 92, he was looking at the results coming from – from Parker that – that it’s more of a marathon than a sprint. And I think that’s really – that’s a really great way to – to live your life.

Dr. Pamela Gay:

Yeah. And – and his Dean at the University of Chicago from when he was an emeritus described him as someone with boundless energy. One of those people who just, like they always say every visionary should do on the internet. He was someone who got up super early in the morning.

Fraser Cain:

Yeah.

Dr. Pamela Gay:

Worked, uh, with – with great – they always described him as “having amazing intuition.” And one if the – the things that I saw that was like, “Oh, that’s not quite work-life balance but I understand.” He had the kind of intuition where if he was in the middle of eating dinner and a thought came to him, he’d wander away to go write it off and then come back to the table.

Fraser Cain:

Yeah.

Dr. Pamela Gay:

And I – I can just, like, – I know theorists like this where all of the sudden they’re off. Okay. The idea – the idea took over. And then –

Fraser Cain:

But that’s experience, right?

Dr. Pamela Gay:

Yeah.

Fraser Cain:

That’s knowing that – that if you don’t get the idea, like, down immediately –

Dr. Pamela Gay:

Yeah.

Fraser Cain:

– then it’s lost forever.

Dr. Pamela Gay:

It’s gone, yeah.

Fraser Cain:

It’s gone. And so, if you don’t capture it at that moment with enough fidelity that you can then explore it in more depth, that’s the challenge of the – of the shower thought, right?

Dr. Pamela Gay:

Right.

Fraser Cain:

That’s the problem. You’re – you’re walking along and you have a good idea and then you’re like, “Okay, this idea is so good that I’m gonna hold onto it now and then I’ll think about it later on.” And then you get home and you’re like, “What did I think of again?” And it’s gone. And you mourn it.

Dr. Pamela Gay:

Yeah.

Fraser Cain:

And so, I think that’s – that’s just purely wisdom and experience to know, “Okay. Idea pops up. I better get it down right away. And even if I have to interrupt dinner, right, to do that.” Because you’re always digesting these problems. And I think back to that – that idea of that work-life balance. Like, I find I only really make progress on some of the more challenging problems that I’m trying to deal with when I’m in a place that is a lot more balanced. And even when I’m doing a task that’s completely unrelated. I can be out in the forest cleaning up, you know, um, brush and go, “Oh, yeah. That’s what I should do.” And then I – and then I have to drop what I’m doing and write it down immediately or it’s gone.

Dr. Pamela Gay:

For me, it’s folding laundry. All my best ideas come to me while I’m folding laundry.

Fraser Cain:

Yeah. Now, he won ever award that you can win pretty much –

Dr. Pamela Gay:

Yeah.

Fraser Cain:

– did he get the Nobel? I don’t think he got the Nobel.

Dr. Pamela Gay:

He did not.

Fraser Cain:

No.

Dr. Pamela Gay:

No.

Fraser Cain:

But he got, you know –

Dr. Pamela Gay:

Everything else.

Fraser Cain:

– everything else. He wrote over 400 papers, which is –

Dr. Pamela Gay:

Yeah.

Fraser Cain:

– just crazy. I mean, you imagine, – like, say you’re writing papers for 40 years. That’s 10 a year. That’s like – that’s a paper a month pretty much.

Dr. Pamela Gay:

So, let’s assume that he wrote papers between age 22 when he got his undergraduate degree and 94. So, that’s 72 years. That’s – that’s four or five papers, some years eight or 10 papers probably, per year and most of us aspire to average one or two a year.

Fraser Cain:

Yeah.

Dr. Pamela Gay:

So, that’s truly remarkable.

Fraser Cain:

Yeah. Multiple books. Like, four books.

Dr. Pamela Gay:

Yeah.

Fraser Cain:

Many are used –

Dr. Pamela Gay:

Textbooks.

Fraser Cain:

– as textbooks by people who are teaching in the field. Yeah. Wow.

Dr. Pamela Gay:

It’s – it’s the correct decision that they named the Parker Solar Probe after him.

Fraser Cain:

Yeah.

Dr. Pamela Gay:

It’s amazing that he got to be there and see it. And to be sharp enough at 94 to understand and want to be part of the research is something all of us can only dream of.

Fraser Cain:

Totally.

Dr. Pamela Gay:

He had Parkinson’s for the last 10 years of his life but his brain was still going.

Fraser Cain:

Yeah.

Dr. Pamela Gay:

And I really am saddened that this is someone who I never met that lived and did research in my lifetime because he seems like a truly amazing human.

Fraser Cain:

Yeah, that’s incredible. Very cool. Well, thank you, Pamela.